Motivation

Usually, in traditional machine learning, we use numerous approaches (model selection) like $K-$fold cross-validation and grid search to find the best model that generalizes well in the real world. However, when it comes to deep learning, it is quite challenging due to compute-cost constraints. It holds for neural language models too.

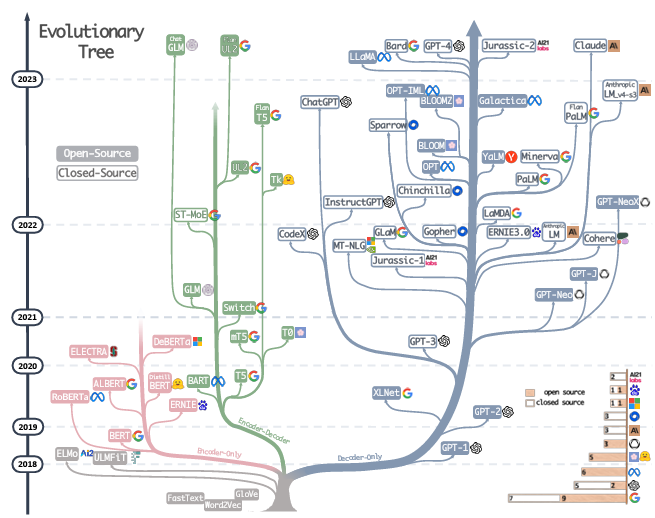

Researchers used transformer architectures to build language models like GPT, BERT and its variants from 2017 to 2019. These transformer-based models outperformed other neural language models like RNN and its variants in most of the language understanding tasks. It is well known that the performance of deep learning models scales well with the data and compute. The word scaling here not only implies increasing the number of layers or the number of parameters (as commonly perceived) but also increasing the size of the dataset and increasing the duration of training time (steps).

Answering questions on the design choices (hyperparameters) would save us huge training costs! Often, we have constraints on the compute resources. We need to optimally use the resources to build a better model as we do not have the luxury to experiment with many variations. For example,

- Is increasing the model’s parameters/dataset size/training duration helpful or harmful to the model’s performance on downstream tasks?

- Whether to Scale the GPT (decoder-only) or BERT (encoder-only) or BART (encoder-decoder)?

- Can we predict all of these even before starting the training process?

- How does loss value change as we scale the model? Can we predict it as a function of other design choices like batch size, training steps and compute budget?

- If we used data parallelism to train the model, then what is the critical batch size?

- For a given computing budget, would you use it to train a larger model for a short time or a smaller model for a long time?

To answer questions like these, one may need to carry out an extensive study with the combinatorial combination of design choices and make recommendations out of it as in [1] and the other way is to come up with simple rules [2] that help us make decisions based on the hyperparameters such as batch size, number of parameters and data size. These two seminal works advocated scaling the model, computing resources and data in tandem. That’s how the era of large language models (LLMs) begun.

Note: This page is a running summary of papers (specifically on scaling) that I have gone through in detail.

Scaling an Encoder-Decoder model

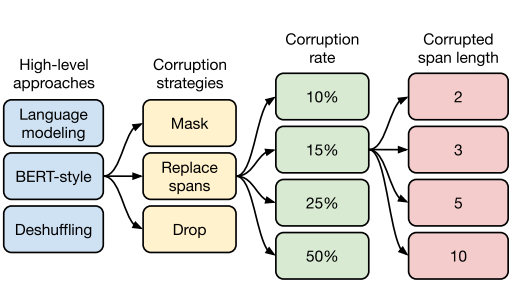

When it comes to pre-train a language model using transformers, there are a lot of design choices such as choosing the architecture type (encoder, decoder, or encoder-decoder), training objectives (CLM, MLM, PLM, deshuffle, denoise), the scale of the model (number of layers, number of parameters, training duration), training strategies (pre-train+finetune, multitask learning) and fine-tuning strategies (adapters, gradual unfreezing).

All of these could influence the performance of the model in various downstream tasks. So it requires extensive study. Fortunately, there is one such study[1]:” Text-To-Text-Transfer-Transformer (T5)[1] ” using a really large dataset called (C4) (of size 750 GB, 156 Billion tokens). Each section of the paper gives you a lot of insights.

Well, the recommendations are the following

- It is not the size but the quality of samples in the dataset that matters

- Prefer *encoder-decoder architecture over encoder-only (like BERT) or decoder-only (GPT) architectures

- Pre-training the model with denoising objective performs better across downstream tasks

- If you want to improve the performance of smaller models (for faster inference), then pre-train the model for longer. (A similar line of study Chinchilla finds the same)

- Underfitting is fine (given the larger dataset, you can barely train for 1 epoch but that is fine)

- (careful) Multi-task training is fine

- Training parameters from scratch is better if you have a large dataset (as in the case of translation tasks)

By following these recommendations, they built a large model with 11 Billion parameters (called T5-Large) and measured its performance. Unsurprisingly, it outperformed SOTA models in almost all downstream tasks! (at that time).

* the current (at the end of the year 2023) trend is to scale the decoder-only models (that is a model that uses autoregressive training)

Well, here comes the decoder-only model (as you might already be aware of GPT-3/4 which is a language model that was released after this study)

Scaling a Decoder Model (Language Model)

Idea: Tune on a few smaller models and extrapolate to bigger ones

Dataset: WebText-2 (40GB,22 Billion tokens) is much smaller than C4 dataset (750GB,156 Billion tokens). Reserve 0.6 Billion toke to compute test loss.

Siz of vocabulary $|V|$:= 50,257

Context window length $n_{ctx}$: 1024

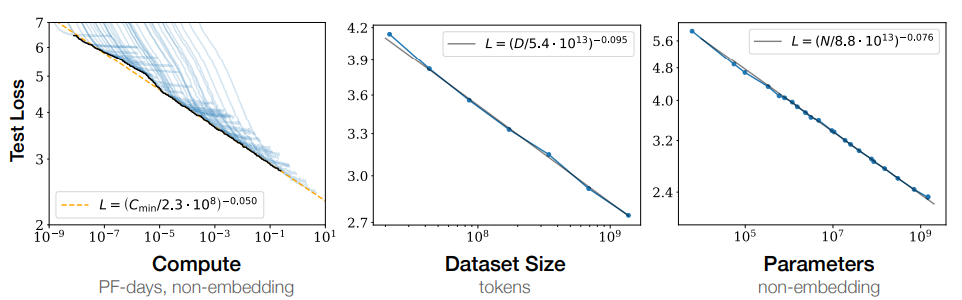

We are primarily interested in finding the relationship among four important factors to the cross-entropy loss $L$ (usually the loss is averaged over the tokens in the context, sometimes it is intra-token loss).

- The number of parameters $N$ (excluding embedding parameters (fixed despite the number of layers in the model) helps establish a cleaner relationship)

- The dataset size $D$ in tokens (roughly equals to number of words)

- Training steps $S$ (1 step of training equals updating the parameters once)

- Compute Budget $C$ in peta-FLOPs-Day (PF-Days=$10^{15} \times 24 \times 3600 = 8.64 \times 10^{19} $ floating point ooperations)

Given $d_{model},d_{atten},d_{ff}$, what is the total number of (non-embedding) parameters?

$N \approx 2 \times d_{model} \times d_{atten} \times d_{ff}$.

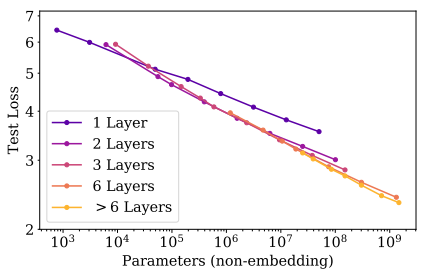

Typically $d_{ff}$ is much greater than the other two. Therefore, $d_{ff}$ contributes more to the number of parameters. So, can we just increase the number of parameters by increasing $d_{ff}$ (keeping the number of layers constant) and expect a decrease in test loss?

Yes, but it observed that increasing the number of parameters works well with the corresponding increase in the number of layers by keeping $d_{ff}$ fixed in all layers. That is, having one layer with 1 Billion parameters performs poorly compared to having the same 1 Billion parameters with 6 layers (The deeper the better! [2]).

Note carefully the use of log-scale for the x-axis (therefore, the relationship is linear on the log-scale).

Given the number of parameters $N$, batch size $B$ and the number of training steps $S$, how much compute $C$ (in FLOPs) do we need?

$C \approx 6BNS$

Important:

If we scale the dataset size, we have to scale the model size and compute size appropriately. For example, if we train a smaller model on a bigger dataset for a longer time, it won’t scale the performance. If we increase the model by $8\times$, then we have to increase the dataset size $5\times$ (Chinchilla differs in this). The figure below shows the smooth performance as we scale these factors

Suppose we train $L$ different models varying in parameters $N$ ranging from $10^3$ to $10^9$ (figure: right) on a sufficiently large dataset $D$ (fixed) and compute budget $C$(fixed). Then the loss could be predicted as a function of $N$

$L(N)=\bigg(\frac{8.8 \times 10^{13}}{N}\bigg)^{0.076}$

Therefore, for $N=10^3$, the loss starts at 6.7886 and for $N=10^9$ (Billion non-embedding parameters), the loss reaches the value of 2.37. Following this trend, it requires 10 Trillion parameters to get the loss value of 1.

Similarly, we can fix $D$ and $N$ (say, $N=10^9$) and vary $C$ (figure: Left). Refer to the paper [2] to know the relationships.

Caution: The precise numerical values of $Nc=8.8 \times 10^{13}$, $D_c$ and $C_{min}$ depend on the vocabulary size and tokenization and hence do not have a fundamental meaning.

Chinchilla Scaling Law:

- Chinchilla recommends scaling the model size (number of parameters) and data size (number of tokens) equally to get optimal performance for the given compute budget. The loss is predictable with the following relationship

Consequences

Well, you might wonder, is there a study on scaling the encoder-only model with MLM (Masked Language Modeling) objective? Yes, it was studied in the T5 paper. However, authors of T5 advocated for encoder-decoder models with the denoising objective and authors of GPT-2 and scaling law advocated a decoder-only model with autoregressive training (CLM objective). Therefore, people started scaling these two models after 2021 as shown in the figure below [4],

We can see five major branches from the root of the three. The third one which corresponds to encoder-only models stopped growing after 2021. The fourth one (encoder-decoder) is competing with the fifth one (decoder-only).

Conclusion

After these two extensive studies, one could anticipate that scaling the models will improve the performance and will eventually require less number of samples for fine-tuning (sample efficiency). These studies motivated to building “Large Language Models” having parameters ranging from 11 Billion (T5) to 1 Trillion (GPT-4).